The National Book Review

2016

Film and Book Review:

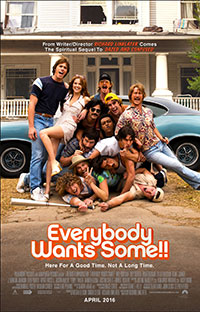

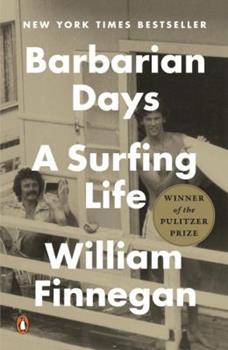

What “Everybody Wants Some!!” and “Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life” Say About Growing Up Male

![]() See the original on-line article

See the original on-line article

Feminist cartoonist Alison Bechdel has argued convincingly that it is high time Hollywood films include at least two women characters having a conversation about something other than a man. Two recent autobiographical works – Richard Linklater’s feature film, Everybody Wants Some!!, and William Finnegan’s memoir Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, which won the Pulitzer Prize in April – spectacularly fail the “Bechdel test” yet brilliantly succeed in their tender, wise examinations of masculinity.

Linklater and Finnegan conjure scenes of male dopeyness, violence, and cruelty to break the omerta of boyhood and expose the mostly hidden internal lives of young men struggling with impossible standards of idealized masculinity. Had Linklater and Finnegan worked to pass the Bechdel test by focusing on complex female relationships, they would have missed opportunities to illuminate the ways boys form friendships with one another that ultimately ready them for emotionally meaningful relationships with women.

* * *

But ev’rybody wants some. I want some, too.

Ev’reybody wants some.

Baby, how ‘bout you?

Richard Linklater takes his film’s title from the music of Van Halen. The band released the song, “Everybody Wants Some,” in 1980, the year Linklater sets his film. It’s an anthemic song that embraces the exuberant sexuality of America before AIDS. Linklater’s choice of song transports audiences to a place and time when it felt great to be young and male (and white and straight).

In interviews, Linklater has described 1980 as the end of an era, a long pause of unparalleled freedom before Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America” and the impending cultural backlash that would vilify stereotypical masculinity and challenge white, male hegemony. Though Linklater is entirely capable of irony (as he showed in his earlier films Dazed and Confused and Boyhood), his take on the ‘80s and maleness is unabashedly respectful and nostalgic. The main character, Jake (Blake Jenner), establishes himself as capable at fuckwithery — a word Jenner has used in describing the movie’s action — as well as genuine insight and intellectual curiosity.

Everybody Wants Some!! chronicles Jake’s first weekend on campus as a freshman pitcher on the college baseball team. Jake arrives at “the baseball house” carrying a red milk crate of LPs, a sure sign of an earlier era. He quickly encounters gorgeous, confident upperclassmen at the house, including the darkly mustachioed McReynolds (Tyler Hoechlin), jubilant stoner Willoughby (Wyatt Russell), and genial wiseapple Finnegan (Glen Powell). Scenes of revelry and competition ensue. The guys break rules and throw wild house parties, hit clubs to dance and cruise for women, and laze about with a bong. They are nearly always together, traveling as a pack. Revelry and rivalry are intertwined, giving Linklater opportunities to set out the rules of game-playing, which are serious to these lads. Jake faces McReynolds across a ping-pong table, the freshman scoring a winning shot. “Good game, man,” Jake says as he reaches out to congratulate his opponent, offering a bicep flexing handshake. A sore loser, McReynolds throws down his paddle in defeat. Another teammate is so addled by egomania that he can’t join in the fun.

Without being didactic, Linklater uses the film to explore the fine line between bullying and boys’ seemingly idiotic merriment. Teammates flick each others’ knuckles to see how much pain they can endure. The older guys Duct tape the new recruits to a fence — and then bat balls in their direction — for what they affectionately call “freshman batting practice.” The teammates compare strategies to get laid, striving to earn points with women and outdo one another. Linklater shows that it is in these scenes of exclusively male play that boys get their rough edges smoothed and lay the groundwork to become interesting men.

To the extent that the film has a plot that moves beyond crotch grabbing and hanging out in a beer-soaked bubble of healthy masculine rivalry, it is in Jake’s budding romance with Beverly (Zoey Deutch). A beautiful, brainy theater major, Beverly captures Jake’s attention early in the film. The baseball guys drive to a dorm parking lot in search of conquests. Beverly rebuffs them. “You should be investing this energy elsewhere,” she chides. “Lesbians!” the older guys reply with conviction.

Offensive? Of course – but that’s Linklater’s point. It’s a set up for Beverly to lean into the car, and declare her interest in “the quiet guy in the backseat.” That’s Jake, of course. “I can see how that could get threatening,” he tells his older teammates. “New guy coming in. Getting all the ladies.” Jake is too new to be making such a joke and takes correction. He doesn’t let the ribbing prevent him from making chase, and later, after he and Beverly have presumably enjoyed an intimacy not possible with random hookups, Jake talks confidently about his college entrance essay, tying his role as a pitcher to the myth of Sisyphus. I won’t spoil the connection Linklater has Jake make, but suffice it to say that there is more to this boy business than beer pong and batting practice.

Linklater has reminisced in interviews that when he was playing college baseball, he spent his time in the outfield longing for more time to read The Brothers Karamazov. Steeped in play, learning the pecking order, the boy will grow into an emotionally literate man who can think, write, and, it turns out, make movies.

* * *

Like Linklater and his character Jake, William Finnegan is an athlete figuring out how experience and literature intersect in Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life. Finnegan is an accomplished lay anthropologist and reporter whose work on politics and war has appeared for decades in The New Yorker.

His title is a riff on a quote from Edward St. Aubyn’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel, Mother’s Milk. Like Finnegan’s memoir, Mother’s Milk is a family story with a main character prone to humorous self-loathing. Describing a young character, St. Aubyn writes that “[h]e had become so caught up in building sentences that he had almost forgotten the barbaric days when thinking was like a splash of colour landing on a page.”

Finnegan suggests that his surfing life is barbaric, not least in the ways its immediacy eludes written language. Born in New York City in 1952 to politically progressive Irish-American, Catholic parents, Finnegan spent his early years in and around Los Angeles, catching the surfing bug in middle school. The bug went viral when the family moved to Hawaii, where rideable swells were no more than a short stroll from his back door.

Finnegan surrendered to surfing’s “deep mine of beauty and wonder” and “knew vaguely that it filled a psychic cavity of some kind.” He was, he writes, “a sunburnt pagan,” torn between life on land and sea. In ten roughly chronological sections, Finnegan builds sentences that, wave-like, propel readers from L.A. and Hawaii through the South Pacific, to Australia, across Asia and Africa, to the Bay Area, to Madeira, and back to New York City.

Reviewers have heaped much-deserved praise on Finnegan’s splendid surf writing, especially a section focusing on San Francisco in the ‘80s. They have focused less on the way the writing paints boyhood in terms of a barbarism that seems to Finnegan, in retrospect, “basic to daily life in a way that seems archaic now.”

In scene after scene, Finnegan describes the violent, scary world of boys, who fight with balled fists and bully unmercifully. Drubbings follow drubbings. “There was no escape,” Finnegan writes, with characteristic humor, of a particular fight, which “went on approximately forever.” Though he was the underdog, he “somehow prevailed.” His opponent “went on to much bigger things, like prison…”

As he deftly paints a Hemingway-esque landscape often populated solely by young men, Finnegan admits that what interests him most is “what was in my head.” His ability to examine his thoughts and feelings defies male stereotypes. Finnegan is as stymied as a female lover when he confronts his macho surf partner’s persistent silence: “For all the intensity of our friendship, and despite our now constant companionship, I always felt, in some basic way, shut out. . . . The old-school masculinity that so many people, including me, found attractive carried with it no small loneliness.”

Finnegan’s loneliness is mitigated by close relationships and literature. Male friendships, from early adolescence in Hawaii to present-day New York, centered on surfing. These are invariably relationships born of a desire to find and ride the best waves around the world. The relationships are enriched by a love of art and ideas. The guys – superb athletes all – know their place in the pack, understand the etiquette of catching waves, and, unsurprisingly, are often game for the kinds of pot- and alcohol-saturated hijinks Linklater so lovingly represents in Everybody Wants Some!!.

The women, meanwhile, don’t surf. Finnegan describes them as brainy, beautiful, and adventurous. They sometimes complain about Finnegan’s close ties to men (one asks, rhetorically, why Finnegan and his surf pal don’t “just fuck each other and get it over with?”), but they rarely seem to express jealousy of his “mistress,” the sea. Like Beverly in Linklater’s film, Finnegan’s women offer opportunities for good sex and conversation. By the time he has committed to his wife, Finnegan has found a way to balance meaningful work, the playful work of chasing waves, and the ability to connect deeply to his parents and, eventually, his daughter, to whom he dedicates the book.

Linklater and Finnegan’s autobiographical tales are wise in the ways of male maturation. “The only way to make a difference with a boy,” psychologists Dan Kindlon and Michael Thompson conclude in Raising Cain: Protecting the Emotional Life of Boys, “is to give him powerful experiences that speak to his inner life, that speak to his soul and let him know that he is entitled to the full range of human experience.” I’m not sure how old boys need to be before parents deem them mature enough to view Everybody Wants Some!! and read Barbarian Days. The sooner, it seems to me, the better.