The Provincetown INDEPENDENT

June 2020

Book Review:

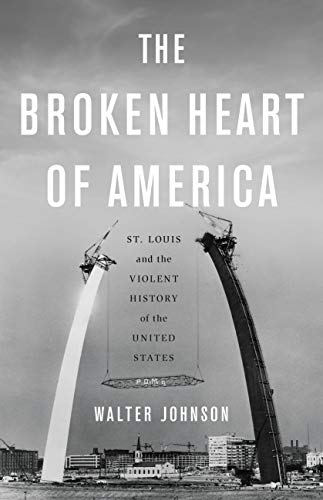

Racism and The Broken Heart of America

Walter Johnson’s history of St. Louis documents the causes of a continuing crisis

![]() See the original on-line article

See the original on-line article

In the months after the murder of black teen Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014, historian Walter Johnson began work on The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States. Johnson grew up in the university town of Columbia, Mo., about two hours west of St. Louis, but, he writes, took for granted the ways his own privilege prevented him from appreciating the city as “the crucible of American history,” not only where the Mississippi and Missouri rivers met, but also at “the juncture of empire and anti-Blackness.” Enraged, he could not help but ask, “What happened here?”

There is a kitchen sink quality to The Broken Heart of America. What doesn’t belong? Readers will encounter the Lewis and Clark Expedition; Indian removal; the Missouri Compromise; Dred Scott; the Civil War; the 1917 East St. Louis massacre; ragtime; a groundbreaking strike led by black women; landmark Supreme Court rulings on housing, education, and employment; urban redevelopment and the infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing complex; civil rights activism; the destruction of black inner-city neighborhoods; and finally the Black Lives Matter movement. The cast includes cultural and political figures from Sacagawea to Scott Joplin to Sonny Liston. He can’t help but mention T.S. Eliot’s 49 trips to the 1904 World’s Fair.When a historian of Johnson’s brilliance and sensitivity asks such a fundamental question, the answer turns out to be neither short nor simple. Johnson, a professor of African and African American studies at Harvard, takes more than 300 pages to get to the actual story of what took place six summers ago in Ferguson. In a riveting prologue and 11 electrifying chapters, Johnson sets American history on fire. He uses as accelerant a concept he describes as “racial capitalism,” a solvent mixing European social theory and the history of America’s slavery-born brand of racism. Connecting episodes from the history of the American West up through the gutting of the black inner city, Johnson argues that America’s lust for land and deployment of the rhetoric of whiteness repeatedly created opportunities for “obscene, spectacular, wanton, joyous” violence, which inevitably led to Michael Brown’s death.

Johnson makes some extravagant claims about how important and sometimes how terrible St. Louis was and is, but his thesis about the city’s centrality is strong without such overemphasis. He also fails to credit a generation of practitioners lumped together as the “New Western Historians.” These folks looked at what had previously passed for histories of the American West and found them racist, classist, and fabulist. That Johnson felt comfortable using the phrase “legacy of conquest” without quoting or anywhere crediting Patricia Nelson Limerick, who wrote a comprehensive book about the U.S. West of this same name, seems downright mean-spirited.

The book is strongest — and hardest to put down — when Johnson moves into the 20th century. I can think of few practicing historians better able to explain the impact of industrial capitalism on a particular place — or how a particular place explains industrial capitalism. Johnson’s treatment of East St. Louis (across the river in Illinois) is masterful. Alcoa, Shell, and Standard Oil set up shop, joining local giants such as McDonnell Douglas, Monsanto, and Mallinckrodt, creating toxic dumping grounds plaguing generations of poor black families. “By the time of the First World War,” Johnson notes, “virtually all of the first families of American capitalism had an arterial tube sucking wealth out of the polluted bottomlands of East St. Louis.”

J.P. Morgan, Jay Gould, Andrew Mellon, John D. Rockefeller, Philip Danforth Armour, Gustavus Swift — in standard accounts, such captains of industry/robber barons create monopolies and rake in wealth, leaving ill-used and poorly paid workers to struggle under the burden of their miserable lot. Johnson does something different with these narratives. He shows readers how liberal republicanism, which he describes as “a white nationalist movement” born in Reconstruction, connects to the racist, individualist, imperial history of the American West. Then he pivots hard to document the complicity and greed of municipal governments animated by racist tax, zoning, lending, and real-estate policies, all of which contributed to the “infrastructure of white exodus.” No accident, he shows, that more than half the towns established between 1943 and 1954 were only for whites who could afford to own homes in the ’burbs.

By the time Johnson is ready to address Michael Brown’s murder, he has demonstrated how and why corporations and governments used weaponized police and predatory lending for “farming [the] poor and working-class black population for revenue.” To be sure, he shows blacks in St. Louis creatively organizing, striking, and protesting all along the way. Johnson prepares readers of The Broken Heart of America to understand the import of one of the last sentences in the book: “The murder of the jaywalking Michael Brown was an acute example of the chronic exploitation, harassment, debt bondage, and wanton bankrupting of the city of Ferguson’s African American population.” He also prepares readers to appreciate the very last sentence of the book: “And still they rise.”